The Scots’ Church Rieger - Part Three: Doing Scots’

The Scots’ Church Rieger - A virtual odyssey

by Stephen Phillips

The third in a series of articles dedicated to what many regard as Australia’s finest church organ – and the story of its hard-won virtualization by Inspired Acoustics.

Part Three: Doing Scots'

For every achievement, there must be a beginning. In the case of complex or lengthy undertakings, it is sometimes difficult to determine, in retrospect, precisely what that first moment of conception was – the thing that would ultimately prove the genesis of the whole enterprise. The plan to document the magnificent 1999 4-manual Rieger of The Scots’ Church, Melbourne, Australia, took shape in a series of at times unintended (and certainly unexpected) opportunities, to be followed by many months of correspondence by letter and phone, complicated by the elements of distance and unwieldy scheduling issues. All this would culminate in a major international effort involving long-haul flights, custom-engineered equipment and a road trip of truly heroic scale.

For every achievement, there must be a beginning. In the case of complex or lengthy undertakings, it is sometimes difficult to determine, in retrospect, precisely what that first moment of conception was – the thing that would ultimately prove the genesis of the whole enterprise. The plan to document the magnificent 1999 4-manual Rieger of The Scots’ Church, Melbourne, Australia, took shape in a series of at times unintended (and certainly unexpected) opportunities, to be followed by many months of correspondence by letter and phone, complicated by the elements of distance and unwieldy scheduling issues. All this would culminate in a major international effort involving long-haul flights, custom-engineered equipment and a road trip of truly heroic scale.

Looking back over the many thousands of hours of work (and kilometres) involved, and the many points of testing of both ingenuity and endurance, the exercise proved a lesson in being careful what you wish for – and how sometimes the difficulties that appear the largest turn out not to be, while others rise to present major challenges, even threatening the viability of the entire project. Certainly, resolve, patience and other virtues worthy of a work conducted in a religious space were to be frequently called upon as the team grappled with its task, the alluring goal ever before them.

The earliest talk of a documentation coincided with our initial introduction to the instrument, which took place during a gap in proceedings at the 2010 ISRA (International Symposium on Room Acoustics) held in Melbourne that year, at which head of Inspired Acoustics Dr. Csaba Huszty was to deliver papers on original research into room impulse response measurement methods, signals and interpretation. It was a typically wet early Spring afternoon – Wednesday, September 1st, when Csaba and myself, in our umbrella-assisted promenade of the city’s various tourist attractions– which, for us, mandated as many organs as we could feasibly take in – at length gained the threshold of the main entrance to The Scots’ Church. My elder brother Peter, a Presbyterian minister and former Moderator of the Assembly, had kindly arranged for us to meet the Director of Music, Douglas Lawrence OAM at the conclusion of the lunchtime service. From our position at the rear of the church, we could hear the organ well enough (especially with the gallery pipework directly above us) but had no clear view of the main case and console. Shortly after the conclusion of the service, and the last reverberant tones of the organ had dissipated, we spied the approach of a bearded, lean man of confident but not purposeful deportment – Douglas was expecting us, and seemed to think our unknown faces and general manner fitted his expectations. Verbal description of the organ had begun well before we reached the console itself, where we were treated to an artful display of the instrument's riches, the rationale behind its specification, and further information on the quest for a suitable builder and all that had followed. Though it is officially the property of the Presbyterian Church of Australia, one might justly make the case for this being 'his' organ – since Douglas, in addition to having long championed the cause for a new pipe organ for the church, was wholly responsible for the design and specification of the instrument, choosing the builder and guiding its construction in an intimate creative dialogue with the craftsmen from Austria given the happy duty of fashioning such a musical masterpiece. The result of this effort, on display that afternoon, is a truly fine organ incorporating elements of English and continental French schools in a thoughtful and seamlessly assured synthesis.

The organ was, from the outset, considered an unqualified success, whether judged in the context of its liturgical functionality or its great versatility in catering to the needs of diverse repertoire and the requirements of touring concert artists. Wholly displacing the earlier organ, this new instrument resides, as before, primarily in the left transept space with additional gallery pipework, accessed from the fourth manual, ensuring a thrilling and immersive tutti experience for the gathered faithful. Douglas, having convincingly demonstrated the instrument’s strength of output and general tonal capabilities, invited us to "explore away" at our leisure. We were to enjoy the great luxury of an entire uninterrupted afternoon with which to better acquaint ourselves with the organ, while of course considering its merits for a possible future documentation. With so many beautiful ranks, and its clear yet liquid articulation of speech, all combining in splendid power, the idea that a wider audience would surely appreciate access to this impressive achievement came naturally.

Following the return to our respective home cities of Brisbane and Budapest, the idea was cultivated to the point that a further visit on my part, in June of 2011, seemed a logically necessary next step. At this time, I discussed Inspired Acoustics’ vision and methods with Douglas, presenting a proposal for a full virtualisation of the organ, together with documentation of the church's acoustics, to which proposal Douglas was evidently favorable. This important early approval – often the primary obstacle to a project's prospects – gave the somewhat misleading impression that all would be 'plain sailing'. With the infamous and treacherous Bass Strait, the undoing of so many vessels across the years, lapping at the shores of Victoria’s capital, I should have known better...

So, we had now to attend to the 'mere' tasks of attaining the official Church approval and sign-off, scheduling time for the work, personnel and all accommodation and daily living arrangements, assembly of equipment and, of course, travel. Shouldn’t be too hard at all…

As it turned out, all sorts of significant impediments would constantly challenge the work’s progress and even ultimate realisation.

The first of these was an understandable by-product of the simultaneous major construction works taking place at the rear of the church, occupying much of the time and attention of the Church’s administration. The simple effect of this distraction was a dangerous (and nail-biting) delay in securing the final signatures guaranteeing legal access to the church and organ. Happily, the relevant documents were ultimately signed, though only just in time. Visa issues were similarly resolved at the last possible moment shortly before boarding. Scary, but solved. The thing could now begin.

When the ‘delegation’ from Hungary arrived at Brisbane International Airport on a crisply fine morning in early May 2012, there was no indication that storm clouds larger and more threatening than those through which we had already past were gathering beyond the horizon. The whole of that first day was dedicated to making final preparations for what lay ahead – a road trip through the heart of the Australian outback, across three states, to our goal at the extreme southern edge of the mainland. The distance, nearly 1,700 km – further than that from Brussels to Madrid – would take two complete days of constant driving, stopping only for fuel, food, and rest (and the occasional herd of cattle). Upon arrival, we would commence work almost immediately. It was important we leave nothing to chance.

Laying out all of the ‘to travel’ equipment before our final pack that afternoon, an unforeseen complication with the structural integrity of a custom tall microphone stand was detected, requiring urgent emergency attention (and inducing no small alarm). Fortunately, my highly skilled friend, engineer Avon Phillips came to the rescue with his expertise and late-night goodwill, opening his machinery factory and hand-fashioning the required reinforcements. Now, at last, it appeared we were set to go.

Making our heavily-laden departure from Brisbane early on a Friday morning, we broke our journey at Parkes, mid-way down the Newell Highway, and briefly at Bendigo (of Gold Rush fame), my birthplace, for afternoon tea/early dinner with my father's sister Rose and her husband Lindsay, finally arriving at our lodgings Saturday evening, full of images of the trip, a little stiff but keen to ‘get on’ with the job. We could not know, at that time, just what that would entail. Enlightenment was but a little way off, soon to make our acquaintance.

Let us pause briefly, while we get our bearings.

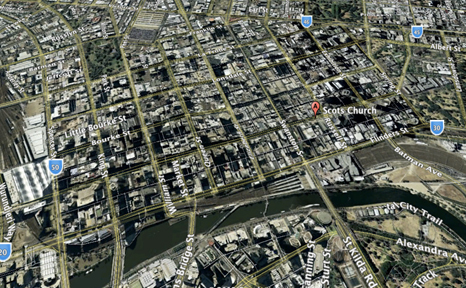

The inner city of Melbourne, designed by Robert Hoddle in 1837, is laid out in a perfect grid, set at an angle favoring the River Yarra's meandering path. Working north-west from the river's northern bank, one encounters a parallel succession of major streets, in between many of which lie the famous ‘little’ streets which might be better characterized as ‘lanes’, thus (in actual order): Flinders St, Flinders Lane (once famous for its fine clothing manufacturers), Collins St, Little Collins St, Bourke St, Little Bourke St, Lonsdale St, Little Lonsdale St, and Latrobe St. These are intersected at right-angles by another sequence of parallel streets, bounded at the south-west extremity by the colossal Southern Cross (formerly “Spencer St”) Transit Station, with the streets running in the order Spencer, King, William, Queen, Elizabeth, Swanston, Russell, Exhibition, and, finally, Spring, on the east side of which resides the architecturally impressive State of Victoria Parliament House. The Scots’ Church is located at the corner of Collins and Russell Streets, on the same city block as the Melbourne Town Hall. Having traveled so far, we were now within striking distance.

The inner city of Melbourne, designed by Robert Hoddle in 1837, is laid out in a perfect grid, set at an angle favoring the River Yarra's meandering path. Working north-west from the river's northern bank, one encounters a parallel succession of major streets, in between many of which lie the famous ‘little’ streets which might be better characterized as ‘lanes’, thus (in actual order): Flinders St, Flinders Lane (once famous for its fine clothing manufacturers), Collins St, Little Collins St, Bourke St, Little Bourke St, Lonsdale St, Little Lonsdale St, and Latrobe St. These are intersected at right-angles by another sequence of parallel streets, bounded at the south-west extremity by the colossal Southern Cross (formerly “Spencer St”) Transit Station, with the streets running in the order Spencer, King, William, Queen, Elizabeth, Swanston, Russell, Exhibition, and, finally, Spring, on the east side of which resides the architecturally impressive State of Victoria Parliament House. The Scots’ Church is located at the corner of Collins and Russell Streets, on the same city block as the Melbourne Town Hall. Having traveled so far, we were now within striking distance.

The next morning we organised ourselves for the work commencing in a few short hours' time, with some last-minute shopping and a carefully prescribed dose of post-lunch sleep. Our schedule had us meeting the church’s caretaker for keys and initial access that afternoon; an unannounced change to the Sunday services schedule had the unfortunate effect of having us arrive too late, to a dark and deserted church, with a cold autumn night descending upon us, along with a squad of local (and well-armed) police, curious at our big car laden with so many... curious... items and standing where no standing is permitted. Several more ‘creative approach paths’ later, having successfully deflected the authorities and made contact with the absent caretaker, we gained our first official access to The Scots’ Church as documenters of the Rieger organ. She waited there, quietly, imposingly, in the gloomy space, barely visible in the muted light afforded by the large stained glass windows. A variety of emotions, as might be imagined, accompanied the depositing of our equipment and first reconnaissance. The long-anticipated time for action had come.

Coincident with these happenings, our colleague Gregory was arriving from Brisbane, having travelled separately (and much more speedily) by plane. We met at Cafe Tono on the corner of Russell and Bourke streets, with the spirited discussion, understandably revolving around the work ahead, only mildly distracted by the excellent Italian cuisine.

That first night was taken up largely with establishing procedures, physical and initial measurements, and a refinement of the specific recording approach to be adopted decided upon with appropriate objective and listening tests. We would now commence the strange cycle of night work/daytime sleep essential to any practical success in the documentation of an organ in as nearly noise-free conditions as possible. At least, we comforted ourselves, this physically depleting cycle would be done within the week, with all data collected and a grateful return to a saner schedule.

It was this “as nearly noise-free” requirement that would ultimately present the chief hurdle to our progress at Scots’. Melbourne, renowned for its many fine churches and extensive formal gardens, was about to reveal another of its less-publicised qualities – the high, unremitting noise levels of a city that "never sleeps"... From the first grim moments of attempted critical recording, it was abundantly clear that “we had a problem”. The great city is a seething monster of sonic disturbance, in all shapes and varieties. In this environment of ceaseless activity, our delicate little undertaking was up against very serious competition. Cars, motorbikes, trams, trains, night road works crews, and (by early morning) a small mobile army of intriguingly task-specific council cleaning vehicles all conspired to make our lives miserable, and a mockery of our efforts to capture the so-elusive pure delicacy of this organ’s many delicious ranks. There was simply no let-up. In all this commotion, it was a significant challenge to find even one single ten second period free of noise – and we had hoped for several thousand! We could see our work stretching way beyond the planned period, and had serious concerns that a meaningful completion might be in jeopardy.

It was this “as nearly noise-free” requirement that would ultimately present the chief hurdle to our progress at Scots’. Melbourne, renowned for its many fine churches and extensive formal gardens, was about to reveal another of its less-publicised qualities – the high, unremitting noise levels of a city that "never sleeps"... From the first grim moments of attempted critical recording, it was abundantly clear that “we had a problem”. The great city is a seething monster of sonic disturbance, in all shapes and varieties. In this environment of ceaseless activity, our delicate little undertaking was up against very serious competition. Cars, motorbikes, trams, trains, night road works crews, and (by early morning) a small mobile army of intriguingly task-specific council cleaning vehicles all conspired to make our lives miserable, and a mockery of our efforts to capture the so-elusive pure delicacy of this organ’s many delicious ranks. There was simply no let-up. In all this commotion, it was a significant challenge to find even one single ten second period free of noise – and we had hoped for several thousand! We could see our work stretching way beyond the planned period, and had serious concerns that a meaningful completion might be in jeopardy.

The best we could do was to plough on... and on...

After more than three weeks of unrelenting efforts, we had finally sampled all of the organ's ranks, along with its own internal action sounds and necessary acoustic measurements. We also had hour upon hour of pristine surround audio of Melbourne’s nightlife, interrupted by abortive attempts to sample a delicate flute or gamba stop against the overwhelming force of a lumbering Collins Street tram or an overly-vigorous cabby (of which there was an apparently endless supply) – or any of the numerous and zealous fleet of nifty little vehicular street-sweepers, gutter-hosers and such like, and which seemed to especially love congregating at our particular corner of the city, just when (exasperatingly) all other noises of the night had begun to recede. Our collective patience and resolve were truly tested.

Sometimes the only thing ‘for it’ was to head to a late-night cafe (with which Melbourne is, fortunately, most well endowed) and wile away the time made otherwise useless by so much sonic contamination. The problem, of course (apart from the logistics of significantly extending our time away) was that the organ is ‘quite large’ and we really had to keep going if there was to be any hope – at all – of completion. At these times, it was only the great prize promised that kept us going. We did even discuss with the (now much friendlier) police and road management authorities the possibility of closing off a portion of the inner city, for the required few hours, to permit some sort of predictability with the environmental noise. While an educational experience, this drastic solution could not ultimately be implemented, due to a mixture of (significant) cost considerations and the time required for adequate preparations. And so, we struggled on. On one occasion, a truck driver positioned his heavily idling vehicle on the opposite side of Russell Street, just after three in the morning. The microphones were very happy to report this situation, with unflagging precision. Running out into the cold night, I found him calmy munching upon a Subway sandwich, quite oblivious to the throbbing roar of his diesel motor – he was 'taking a breather' before his next assignment. Gaining his attention, I politely asked if it might be possible for him to munch elsewhere, a proposal he (thankfully) was more than open to. Less negotiable was the small-squad road crew which, deep in the night, simply had to cut and torch a particular square of asphalt right there, outside the church, while we shook our beyond-weary heads within, doing out best to look for the humorous side to this increasingly crazy predicament. It may well be that there, in that precise time and place, we were involved in the all-time simultaneously most-ludicrous and arguably most-valuable documentation effort yet to be undertaken south of the equator. Foolish? Vain? In our hearts, we knew otherwise. In our collective understanding, we begged to differ. We knew, with the deepest sense of assurance, that our (perhaps increasingly enfeebled) efforts served a greater end, and a higher cause.

Our last morning at Scots’, to record video of Douglas at the instrument and withdraw all remaining equipment, tangibly reminded us of the value of the suffering we had endured through near one month of dogged determination, against every and all odds. Here was the beautiful Rieger organ, in the hands of the master musician who had given it the chance of life, sounding in gloriously full voice, careless of the agitated and bustling central-city turmoil just beyond the beautiful stained glass windows and the instrument's own lustrous wooden casework ingeniously retained from the organ’s immediate predecessor. As Douglas Lawrence had wrought a minor miracle in giving the city its finest church organ, we too had conquered a string of (at times, very) serious besetting obstacles in capturing its extraordinary essence in digital form, now ready to begin the lengthy process of making of all this data a coherent, playable virtual instrument. This story, a saga in its own right, demands, and will form, the fourth and final episode of this series of articles. In the partly artistic, partly scientific work ahead, advanced custom-engineered processing algorithms would ultimately see first-time deployment as a major component in maximising the usability and quality of the sample material – and consequent end result – in this important new virtual organ from Inspired Acoustics – The Scots’ Church Rieger.

Our last morning at Scots’, to record video of Douglas at the instrument and withdraw all remaining equipment, tangibly reminded us of the value of the suffering we had endured through near one month of dogged determination, against every and all odds. Here was the beautiful Rieger organ, in the hands of the master musician who had given it the chance of life, sounding in gloriously full voice, careless of the agitated and bustling central-city turmoil just beyond the beautiful stained glass windows and the instrument's own lustrous wooden casework ingeniously retained from the organ’s immediate predecessor. As Douglas Lawrence had wrought a minor miracle in giving the city its finest church organ, we too had conquered a string of (at times, very) serious besetting obstacles in capturing its extraordinary essence in digital form, now ready to begin the lengthy process of making of all this data a coherent, playable virtual instrument. This story, a saga in its own right, demands, and will form, the fourth and final episode of this series of articles. In the partly artistic, partly scientific work ahead, advanced custom-engineered processing algorithms would ultimately see first-time deployment as a major component in maximising the usability and quality of the sample material – and consequent end result – in this important new virtual organ from Inspired Acoustics – The Scots’ Church Rieger.